A word about cryptolinks: we are not responsible for the content of cryptolinks, which are merely links to outside articles that we think are interesting (sometimes for the wrong reasons), usually posted up without any comment whatsoever from me.

Don’t believe everything you read on the internet,

despite what cryptozoologists may be telling you.

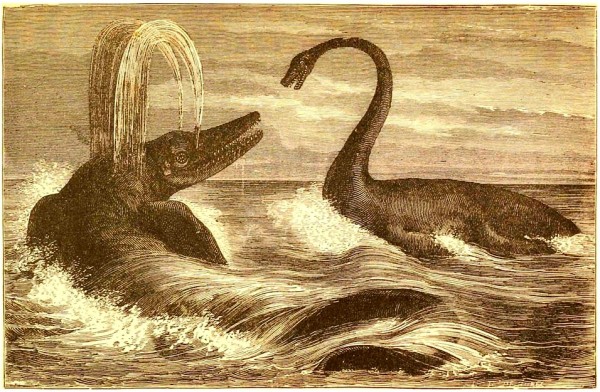

Plesiosaurs, like mermaids, Megalodon, and a representative democracy, don’t really exist anymore, but Baird’s Beaked Whales do, and you’re looking at one.

The internet is a double-edged sword of enlightenment and ignorance. It has the capacity to educate millions in ways never before possible, making science accessible, understandable, and relevant. At the same time it infects the public with idiocy, lies, pseudoscience, and the malevolent intention to mislead (kind of like Discovery Channel). Disinformation is a zombie. It is the resurrected body of mysteries solved, arguments settled, and bad science disproved, marching through half-baked websites and ‘shared’ by newly-infected readers not yet schooled in the truth, spreading fabrications and misinterpretations that eat away at the integrity of science and numb the brains of the masses.

Among the many internet zombies gnawing on science and pseudoscience blogs, the one I’ve battled is the “mystery’ of the “Moore’s Beach Monster” (sometimes called the “Santa Cruz Sea Serpent”), touted as a living plesiosaur in the modern world, a remnant of the age of dinosaurs in the 20th Century, and proof that ancient beasts still live among us. It has become a perennial icon for conspiracy-paranoid cryptozoologists and fundamentalist creationists. In fact, there never was a plesiosaur, and even upon its discovery, the remains of a decomposing beached carcass was shown most definitively not to be a plesiosaur, but dozens of internet sites still push the plesiosaur hoax. I get enough inquiries about the reptilian validity of the Moore’s Beach Monster every year that even the Travel Channel tried to help me debunk it in an episode of Mysteries at the Museum.

From the time humans walked on two legs between the beach and the tides, and after the first of our ancestors took to the ocean, “sea serpents” were commonly observed at sea or cast upon beaches, celebrated locally and later ingrained into regional lore. During the 1800s and 1900s, the advent of cameras recorded these events in grainy sepia-toned images, some real, some retouched. The immediacy and broadcast of newspapers brought these sea monster sensations to a wider audience and heightened celebration of such mysterious beasts. These were the grotesque remains of otherwise normal animals that fear, ignorance and imagination transformed into nightmarish beasts.

No comments:

Post a Comment